Saturday, September 17, was the fifth anniversary of the first day of Occupy Wall Street – two months of protest against economic inequality, based in a small plaza in Lower Manhattan known as Zuccotti Park. The movement spawned other Occupy protests from Seattle to Miami and launched an unstoppable revolution to stand up for the ninety-nine percent for whom the economy doesn’t work.

For the organizers in New York, as for many of us, when you are committed to social justice, you cannot help but raise your voice in the face of racism, classism, and many other institutionalized behaviors that casts one segment of society as less worthy of the respect of humanity than another.

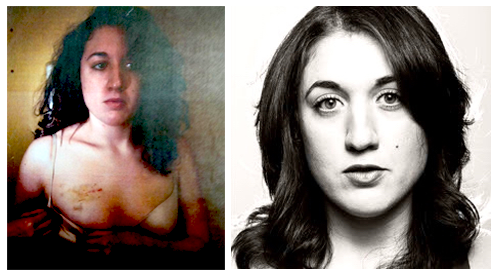

This is the story of one self-described “Occupy die hard,” Cecily McMillan. She is the young woman who, after being violently assaulted by the New York Police Department during a peaceful, Occupy Wall Street six month anniversary event in 2012, unintentionally became the face of the movement when she was arrested and went on trial for assaulting the cop who grabbed her breast and beat her until she bounced on the pavement, writhing in seizure.

It was supposed to be a quick visit, a show of support before heading out with friends to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day, but it turned into something much worse.

“The only thing I am guilty of,” she would later say, “is not going in with a partner. I should have known better.”

VIDEO: Cecily McMillan’s friends stand across the street and watch her getting attacked – 3/17/2012

VIDEO: Cecily McMillan rolling on ground before put in ambulance – 3/17/2012

VIDEO: A bruised Cecily appears on Democracy Now days after her arrest – 3/23/2012

and a more recent portrait (Steve Eberhardt)

“In encountering struggle, you realize the stuff you are made of.”

– Cecily McMillan

After a short trial with a difficult judge, a jury convicted McMillan of the assault. But there was an outpouring of support, including from three-quarters of the jury itself, pleading for leniency, and instead of the two to seven years she could have gotten, the judge sentenced her to three months in jail and five years of probation. She is now a felon. Part of the terms of her probation is that she is not allowed to participate in any protest or civil action.

This, admits Cecily, is difficult for her, as she only found her own freedom in fighting for others. She describes her passion for equality as “the accountability of activism.”

“Accountability,” she told me during a recent conversation in an Atlanta park, “that’s what I tried to foster in the cadre [of Occupy activists].” That was important in a movement that famously had no leaders precisely because they expected committed activists to step up and do what’s right.

“It’s good to do your best in your capacity, and to inspire people to be as accountable to others as you are,” she explained. “If we think of Martin Luther King [Jr.] as somebody special, nobody steps up in his place once he goes. Who could fill his shoes? If people think I’m special [for being willing to fight for justice and go to jail], then they say, ‘Well, I don’t have to do what she did.'”

Let’s be clear. Cecily is not comparing herself to MLK. She is saying that the willingness, the capacity to fight for equality and justice, is in each of us. Activists have to believe that. Otherwise, why show up? We stand neither as hero worshipers nor heroes, but ordinary people inspired by those who came before to take a public stand for social consciousness.

McMillan has a story to tell about a life that began with her fighting for herself, and evolved into a fight for the welfare of others, because, as Dr. King said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Sometimes we see injustice in the ugly way we treat each other as human beings, like in an outsider who is shunned by social divisions, and only requires what all people do – love and acceptance. Sometimes injustice is what one sees in a misguided community’s visceral reaction to a cultural event or tragedy.

While Cecily’s undeniable empathy brings her to the side of the former (she almost went to jail for trying help a Hispanic couple avoid it themselves), it is for her communities that her voice is loudest and her defense is strongest. It is there where she had her awakening.

While Cecily’s undeniable empathy brings her to the side of the former (she almost went to jail for trying help a Hispanic couple avoid it themselves), it is for her communities that her voice is loudest and her defense is strongest. It is there where she had her awakening.

It happened in the small Southeast Texas town of Beaumont, after September 11, 2001. She was days away from her thirteenth birthday, and, as she writes in her recently published autobiography, The Emancipation of Cecily McMillan: An American Memoir:

“That was the first time I’d heard the word ‘terrorist.’ …The terrorists, I learned, had been Muslim, so they believed in Islam; which, I was told, was a religious cult of brown men with towelheads and long beards who worshiped war, enslaved women and hated Christians.”

It was the prevailing perspective in a small, poor, segregated, southern town, that, to McMillan’s credit, she admitted “sounded crazy to” her. More to the point, she was aware enough to begin questioning the norms of her community:

“I was at a pep rally for an upcoming football game. The cheerleaders had just performed a routine to Lee Greenwood’s ‘God Bless the USA’ when an athlete grabbed the mic and said, ‘This one’s gonna be for the troops – tonight we’re going to go out there and kick ass like they was sandniggers!’ The gym went wild…”

It was the suffix, as it were, of the epithet that drew her attention. “I’d never heard that word used for anyone but blacks,” she wrote. “What did it mean that it was so easily transferable?”

“When I started asking questions, I realized it wasn’t enough to be white and Christian,” McMillan told me. “If you disagreed with them, then you might as well be with the n*****s and the people who weren’t Christian…

“I was white, and I was Christian, but just because I started to ask questions, then all of a sudden, I didn’t get to be part of their club anymore.”

It was shortly after that when she took her first action for social justice. As she writes in the book:

“One day, I stayed seated for the Pledge of Allegiance and stood up when everyone else sat down for the moment of prayer. When the teacher sent me to the office, the principal wanted to know why I’d done it. ‘Because,’ I explained, ‘some people aren’t Christian, but we have to say “under God” in the pledge and worship him in prayer.’ ‘Don’t you believe in God?’ he asked. ‘I do,’ I replied, ‘But that’s not the point.’ ‘Then what is?’ he asked. ‘That you make us do it…What if I wasn’t Christian?’ ‘But you are Christian.’ he replied. ‘But if I wasn’t,’ I argued, ‘it would be wrong to make me worship a different god.’ ‘Yeah, well, you’d also go to hell. Do it again,’ he challenged, ‘and you’ll get a taste of it.'”

The “taste” of hell, when she repeated her protest the next day, was a paddling. That evening, she says, she wrote in her journal:

“They think they can put me in my place, but they can’t. My place is wherever I say it is.”

“You know, Millennials, we were never really afforded a childhood, as a generation. Our generation did drugs to fit in, not to chill out, not to party. We did Adderall, to go to school more, to get there earlier, to stay later, to do all sorts of extracurricular activities – to be all perfect, a perfectly well rounded human being…

“We were made into neurotic little yippy dogs, all of us.”

– Cecily McMillan

It would be easy to dismiss Cecily McMillan as just another youthful radical, naive of the compromises other generations made in battles deemed too destructive to keep fighting. On the other hand, I found her to be the real deal – as authentic and caring an activist as I’ve ever met.

She describes herself as “really working class.” Sure, she cites revolutionary thinkers like Foucault, Badiou and Michelle Alexander the way Lit majors cite Shakespeare, Bronte and Huxley, but it’s not just an academic exercise for her. It’s her strong belief in the words one of her college professors told her, that “Teachers are society builders.” Her passion brought her to learn more, and her learning inflames her passion.

“The college and the prison chapters [of the memoir] are probably the two that are least defined,” she said, thoughtfully, “because I’m still working on what privilege is and how it was taken away from me.” She went on to explain that to be raised in poverty and be given an opportunity to attend college and be free to embrace activism, and to become “Activist Barbie,” as the media called her during the trial, and then to lose that and more – including the respect of her family – when she went to prison, has left her and her family more estranged than ever.

“There’s something truly painful,” she lamented, “about being in privilege, for people who were not raised with it, because in gaining privilege, you lose your family; you lose your identity; you lose your culture. It’s painful.”

Cecily’s family has names for her, she says, like “pretentious, highfalutin,” and what is perhaps most hurtful, “not a McMillan.”

The confusion, for her, was escaping the fate of many raised in poverty in America. “What,” she asked me, rhetorically, “so I gained the privilege to not become a heroine addict? I gained the privilege to not starve to death?

“I gained privilege, but I worked myself out of [the] family, out of roots, out of soul.” For her, not being able to return to the culture in which she was raised has left her with what she now sees as two unpleasant choices: privilege or prison. In her mind, she either violates her principles of equality and pursues money, or goes back to a life of protest and civil action, and loses her freedom. Either way, her family resents her.

Still, she believes, prison is the key to “breaking” our society – not in the anarchistic sense, but in the sense of breaking a dysfunctional addiction to institutionalized thinking. “Anybody who’s in college or a PhD program right now ought to be in jail,” she argued, “and I think everybody that’s in jail ought to be in college.” Later, she clarified, “Let’s leave college alone. Let’s say anybody who’s in a masters or PhD program, their time would be better spent in jail.”

This will, McMillan claims, allow those in higher education to have practical experience, to learn and to write about what they’ve only studied in their “ivory tower” of theory. “They [already] know how to study that. They don’t need a guide.” They need the experience.

On the outside, she says, even if you’re involved in an action as bold as Occupy Wall Street, “You are the privileged allied with the oppressed.” But in jail, she went on, “You are the oppressed allied with the oppressed. You are the oppressed and the activist.”

If you’re young, living with you parents and not making any money, “What have you got to lose?” she asked. “Go to jail [for what you believe]. How much can you do on the inside? Guys, you’ll be fine.”

Cecily says flipping the script is something Millennials are poised to do. The economy and our social structure demand it, because the class entitlement they grew up with – money, segregation and/or education – is no longer relegated to provincial America.

“I love my generation,” she told me, hopefully. “We’re really entitled, but that entitlement is going to be this world’s saving grace. When we’re the poorest people [living in neighborhoods] alongside those that are currently ‘othered,’ right now, with the education that we have and the entitlement we have, we are going to put upon the world entitlement for all, and that’s going to be huge.”

For McMillan, the opportunity for the entitled to learn about what it’s like to be without food, housing or a job, “or a good life,” will necessarily bring those universal requirements to all. “‘Entitlement for all,’” she reflected, adding, “I love that.”

(Kevin Zeese)

“I came up with this idea in prison that I still believe in. I don’t believe any of us are any freer on the outside than those on the inside. We just have more distractions.”

-Cecily McMillan

That brings us to the question just about anybody might ask her. (I did.) Why does someone in their mid-twenties need to write a memoir? After all, it wasn’t as if she were some kind of radical wunderkind.

“Oh my God, I would have slapped the shit out of myself in the sixth grade,” she told me she realized after consulting some of her old journals for her story.

But the message of the book, she says, isn’t the narrative of her perseverance throughout her challenged childhood, or her ordeal at Occupy Wall Street, or at the hospital, or in court, or even in jail.

Cecily told me many times how uncomfortable she was that the redemption in the story was about her. “People are still just really into me, in the most delegitimizing way,” she lamented. “People want to talk about me. People want to spectacle-ize me. They think, ‘Oh well, you wrote a book. How bad could your life be?’ Really bad,” she concluded, emphatically.

The message she wants to get out is that it is precisely because of her challenges growing up poor, in a broken home with parents always screaming at each other and crying, a suicidal, depressed mother and a severely ADHD brother who was later diagnosed as bipolar, that she was able to put up with her ordeal both before and after the events of March 17, 2012, in New York.

“This book was the first time I realized how much of my life was not accessible to the people [at Occupy] that I had wanted to be – previously – a part of,” she admitted.

Given that version of privilege, the privilege of conditioning, we could call it, Cecily claims it was easier for her to understand the plight of the women with whom she was incarcerated in the jail complex at Rikers. She called it a shared “generational history” of those most challenged by the classism in our society.

“I wrote this book for the women at Rikers,” she said. “I promised them that I would do everything in my power to make sure their demands were heard and their lives were, to the best of my ability, protected. Not just the women I served time with – the women of Rikers generally.

“The only goal I have with this book was to get people to see prisoners as people.”

In the book, McMillan describes the facility and its location starkly:

“The East River is a salt-water tidal strait that flows northward along the eastern shore of Manhattan Island, then bends due east between the Bronx and Queens before returning to the Atlantic. Just past that eastward bend, with Queens to the south and the Bronx to the north, lies Rikers Island, a hard to get to (and harder to get out of) outpost of cruelty and misery, just across the water from LaGuardia Airport. The island is flat and treeless and surrounded by razor-sharp barbed wire fences; its only link to the mainland, the Elmhurst neighborhood of Queens, is a narrow causeway.”

At intake, she describes the beginning of the metamorphosis from celebrity defendant to convict:

“When I went in, Activist Barbie [in the form of the fashionable dress worn at sentencing] (still entombed in the plastic Nordstrom bag) was taken from me and disposed of ‘in the back,’ where she was then exhumed and dismembered, according to the property receipt I received in exchange…the only remaining records that she’d ever existed – that I’d ever been a person worth defending. Now, I was just a prisoner.”

The other prisoners, McMillan said, wondered why she was in there. They never expected a white girl to be sentenced to Rikers, but they didn’t know her mother was Mexican until she spoke to them in broken Spanish, when they asked if she was loca, a familiar term from her abuela. “No siempre (not always),” she told them.

“I was one of five white women in Rikers,” she said, “and all of us were half-Latina. There are not white people in Rikers. There’s not even white corrections officers.” One of the other Latina prisoners took Cecily under her wing, and became her “jailhouse godmother.”

“I was totally happy there amongst those women,” she told me. “They are the best human beings I have ever met in my life.”

Then she added, “Prison, in a way, is the great equalizer. Being in there, you’re all just fucking prisoners, man. You have a single enemy. You have a single structure that you’re all against. And it’s not the COs [corrections officers]. It’s the captains. It’s the doctors.”

In the book, she describes how prison psychiatrists refused to give her a new prescription for Adderall to treat her ADHD. Then, in terribly disturbing detail, she tells us about trying to get her Depo-Provera shot for birth control, and that the gynecologist insisted on a needless vaginal exam – twice – for a pap smear and a scrape. She left in tears, and without the shot.

Her prison sisters told her to leave it alone, that in Rikers, “you don’t ask, ‘Why?'” But being the accountable activist, she wrote her lawyers about the incidents with the doctor, and finally got her birth control and her Adderall.

“See,” she told her friends, “this is what happens when you ask, ‘Why?'”

They looked at her and said, “No. This is what happens when you ask, ‘Why?'” Their experience of questioning the system never turned out as well.

To be sure, McMillan experienced hardships in prison, but there was something about being in Rikers that, she admits, made her wonder whether she would be better there than on the outside.

“Things are just a lot more real in there,” Cecily explained. “I’m not somebody who likes grays. I like black & whites. I like to know who the enemy is. I like to know what the obstacle is. At least in there, you know. You can see it. Here it’s just a series of delusions. I can drink [a beer] and feel a little bit better, but I think we see freedom when more people like me go to jail. It’s clarity. It’s really realizing that the only freedom you have is the dignity to choose your outcome, the dignity to go about life that you can look in the mirror every day and say, ‘I’m doing my best.’ That’s the only freedom. When the only thing staring back at you is hate and you choose to love, that’s freedom.”

“I am literally the least likely at Occupy Wall Street to write a book.”

-Cecily McMillan

Since her beating at the hands of police, Cecily suffers from PTSD, including symptoms like blackouts, breaks in memory and night terrors that leave her “petrified, like breathing is hard,” and “scared – really, really scared.”

Despite that – or, she might argue, because of it – she remains an inspiring example of what it means to be an activist.

“When you think you are better than people, morally or whatever, it’s no better than the Trump people who think they’re better than the Mexicans,” Cecily reflected. “You can’t inspire anybody when you think you’re better than them, and I did not inspire my comrades at the New School [graduate school in New York, during Occupy] to get involved with Occupy Wall Street because I thought I was better than them. And you know what? That’s shirking my fucking duties. That shut down conversation, when your only job as an activist is to foster conversation.

“You are an activist. You are actively affecting the world. And when you call yourself that, you are taking a-count-a-bi-li-ty,” she enunciated, “for how you actively impact the world. That’s what [being] an activist means. And then, people can call you out on your shit, people can judge you and people can critique you and you can judge and critique yourself.

“You have to be responsible for that. You are no longer reactive. You are no longer unconscious. You are responsive, you are engaging and you are accountable. And if you are not doing that, then you are a bad activist. Period.”

That’s a high bar, for most, but the example of Cecily McMillan’s commitment is as much aspirational as it is inspirational. If you’re going to put yourself out there, then do it. Notice when you’re not doing it and “judge and critique yourself.” Acknowledge your humanity, give yourself permission to fail, and find a different way. But don’t lose your inspiration and don’t lose your determination because fixing the world is everybody’s obligation.

-PBG

PS. Cecily also had something to say about Atlanta and its Occupy event, as well as the city’s role in the revolution. Check it out on my Daily Kos diary.